|

Back in the days when the West believed it was in imminent danger of being swept away by the Communist menace (before the collapse of the Berlin Wall necessitated the invention of the Islamic menace), books about the Soviet Union and its nefarious plans were both a dime a dozen and indeed ten a penny. Here's a few of wildly varying quality.

Let's start with the mad Americans. None Dare Call It Treason by John A Stormer (crazy name, crazy guy) came out of the South in 1964 and was a raging success - this is the twentieth edition from that year, bringing the total number in print, if its figures are to be believed, up to 6.8 million. Its message is summed up on the back in words that could serve as a plot summary of Invasion of the Body Snatchers:

They have infiltrated every conceivable sphere of activity: youth groups; radio, television and motion picture industries; church, school, educational and cultural groups; the press; national minority groups and civil and political units...

When he says 'they', of course, he means commies of all descriptions: secret agents, fellow-travellers, dupes, the whole damn lot of them. You won't be entirely surprised to know that this concerned citizen is particularly scathing about attacks in the communist-infiltrated press on such decent institutions as the John Birch Society. You also won't be surprised to learn that he's a white man from Missouri.

None Dare Call It Conspiracy is effectively the same book eight years on, since somehow American capitalism had still not fallen in the intervening period. If anything, it's a tad more extreme, seeing Nixon and the Black Panthers as being essentially on the same side, attacking the decent middle-class. The really baffling thing about both these books is the deep insecurity they reveal: did white America really feel that threatened, that uncertain that what it had to offer could survive a bit of competition? Yes, is clearly the answer.

The Overstreets' earlier What We Must Know About Communism (first published in 1958) is slightly less barking, but still starts from the same position that somehow consumerist democracy is a fragile flower in danger of being strangled by the foreign weed of workers' control. It does, however, provide a basic over-view of the evolution of communism, explaining, for example, the historic role of the Internationals: the interpretation is extravagantly one-sided, but for a country that sometimes seems to pride itself on its ill-educated masses, a little learning is a slightly less dangerous thing than pig-ignorance.

In short, all three books are great fun, and packed full of inadvertent insights into the metapsychology of a nation ill at ease with itself.

I know nothing about Comer Clarke, save that he went through a busy little period of writing books (The Savage Truth about Eichmann in 1960, this one, then If the Nazis Had Come in 1962 and We, the Hangmen in 1963), before disappearing from vision. The prose is unispired, and the subject a bit specialist, but it does have a few pictures, including this one of a café in Lower Marsh Street, Waterloo. Apparently it was pretty much wall-to-wall enemy agents in there, but it looks like it could have come from the pages of Generation X.

Vastly superior to any of these is Inside Red Russia, in which a member of the Australian Labour Party relates his experiences of spending two years in the USSR. It's all pretty horrible, including stuff that has since become commonplace - censorship, industrial and agrarian exploitation, labour camps and so on - though the fact that he was there in 1943-45, during the Great Patriotic War, does mean that the conditions he describes could be excused by apologists for Stalinism as being exceptional.

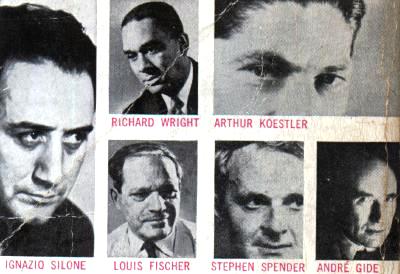

Mr Maloney's account is given additional weight by virtue of his position within the trade union movement: he should in theory have been a sympathiser if not a supporter, and his disillusion is a major part of the story. The same is true of the final volume here, The God That Failed, first published in 1950 (i.e. before Kruschev's epochal intervention at the 20th Party Congress and before Hungary). A genuine classic of 20th century politics, this compiles the personal experiences of six leading writers and their growing disenchantment with Communism. Unlike the authors of the None Dare Call It... books, these people have the benefit of both intelligence and direct experience of their subject. Arthur Koestler's chapter, in particular, is essential reading, to be followed immediately by his novel about the Moscow show-trials, Darkness at Noon.

home |